Blocking Inflammatory Pathway Reduces Blisters in EB Simplex Generalized Severe Patients

Written by |

A specific class of T cells – called Th17 cells — may drive inflammation in patients with epidermolysis bullosa simplex (EBS) generalized severe, and targeting these inflammatory pathways might lessen blistering in these patients.

The study, “Epidermolysis bullosa simplex generalized severe induces a T helper 17 response and is improved by apremilast treatment,” was published in the British Journal of Dermatology.

EBS generalized severe is caused by mutations in the genes keratin 14 or keratin 5. The proteins encoded by these genes help give cells their shape, so it was long thought that disease symptoms were caused by mechanical issues with cell fragility.

However, recent studies have suggested that this mechanical phenomenon doesn’t totally explain the progression of the disease. Inflammation also seems to play a distinct role.

In an attempt to address how inflammation influences EBS generalized severe, researchers in France studied skin and blister biopsies from patients. These included stored samples dating back two decades, as well as samples from patients who were enrolled in a small prospective arm of the study, for a total of 22 biopsies from 17 patients. Skin from healthy volunteers on whom artificial blisters had been induced was used as a control.

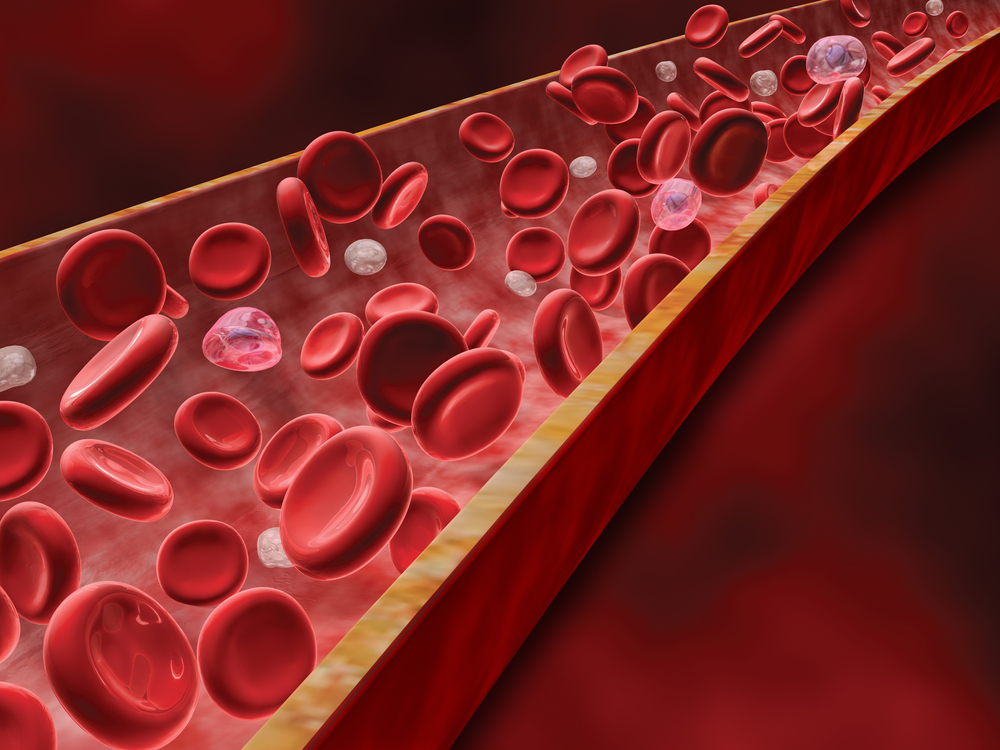

The researchers found that there were inflammatory immune cells present in all of the biopsies. Further investigation revealed a particularly high proportion of CD4+ T cells. Broadly speaking, these cells don’t directly attack invaders or other cells; rather, they secrete chemical messengers — called cytokines — to help coordinate the body’s defense against a perceived threat.

The researchers investigated the cytokines in these samples in detail, and found that a certain class — Th17 cytokines — were expressed in all EB patient samples.

Th17 cytokine-driven immune responses are, fittingly, associated with the presence of Th17 T cells, which are a subset of CD4+ T cells often involved with driving inflammation.

“These data strongly suggest the involvement of the Th17 immune response in the pathogenesis of [EBS generalized severe],” the researchers wrote in their paper.

They further tested this idea by conducting a small trial where three patients were treated with apremilast (brand name Otezla), a drug that targets Th17 cells and is approved for psoriasis treatment. The patients were given increasing doses of apremilast, from 10 to 30 mg twice daily, and the number of blisters decreased substantially over the course of one month.

Side effects included abdominal pain and diarrhea early in the treatment, which eventually stopped. One patient stopped treatment after seven months because of nausea, and had a recurrence of blistering two days later. The other two patients reported no further adverse events and had seen no recurrence of blistering at eight and 10 months.

This is a very small first step, and further studies with more patients — as well as more thorough investigation of disease progression, rather than just observations of blisters – may pave the way for apremilast or other therapies targeting Th17 immunity being used to treat EBS generalized severe patients.

In an accompanying editorial, Jemmina Mellerio, lead for the Adult Epidermolysis Bullosa Service at the Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, wrote that this study provides “tantalizing evidence of a more specific targeted therapy for the inflammation and blistering

seen in this type of epidermolysis bullosa.”

She adds that “a systemic therapy in the form of apremilast, and perhaps other anti-IL-17 agents” could avoid “the problems of topical delivery to blistered skin or the need for application over large areas pre-emptively to prevent blistering.”