Donor-derived Skin Grafts Feasible Way of Treating RDEB, Trial Reports

Written by |

Transplanting skin grafts from healthy donors can be a safe and effective way of treating chronic wounds in people with recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa, a small clinical trial shows.

But to create immune tolerance and prevent the graft from being rejected, patients first need to receive a stem cell transplant from their donor. These cells also appear to contribute to wound healing in the long term, researchers said.

The study with the findings, “Immune tolerance of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation supports donor epidermal grafting of recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa chronic wounds,” was published in the British Journal of Dermatology.

Epidermolysis bullosa refers to a group of rare and inherited skin disorders that make the skin extremely fragile and prone to blistering. RDEB is caused by mutations in the COL7A1 gene, which contains instructions for making a key protein for skin integrity called type VII collagen (COL7).

The chronic wounds that result from RDEB contribute to significant pain and itching, and are also common sites for the development of infections and skin cancer.

Skin grafting is a promising approach to heal chronic wounds in these people. But patients cannot receive grafts from themselves — due to the lack of skin integrity throughout their body — and grafts from donors have limited efficacy as the host’s immune system often rejects the transplanted tissue.

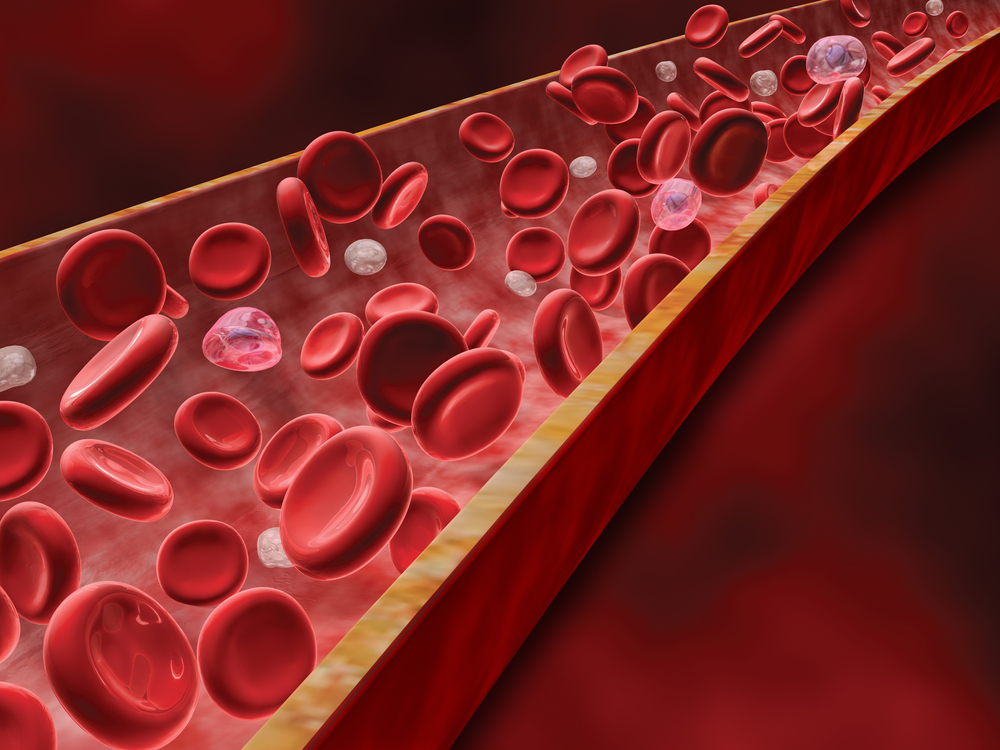

Undergoing a blood stem cell transplant from the graft donor could potentially solve this problem. With this approach, patients can have two sets of bone marrow stem cells generating immune cells — their own and the donor’s; a setting called chimerism. The presence of immune cells from a donor helps to create immune tolerance, allowing patients to be given skin grafts (or any other organ) from the same donor.

To validate this approach, researchers at the Masonic Cancer Center, University of Minnesota, conducted a small clinical trial (NCT02670837) involving eight patients and a total of 35 skin grafts. Participants, a median age of 8.7, received their first graft about three years after the stem cell transplant.

Each patient received grafts for a maximum of nine chronic wounds. Grafts, measuring 5 cm² each, were applied in three sessions, about 12 weeks apart, with up to three treated wounds at each session.

For this trial, grafts were harvested from donors using the Cellutome system, which provides uniform pressure suction and heat to efficiently separate the skin’s top layer (epidermis) from the bottom layers, without need for anesthesia or surgical skills, the investigators said.

Notably, the device harvests 128 micro grafts, spaced 2 mm apart. This allows for minimal pain and rapid recovery of the donor.

Results showed that the skin grafts significantly reduced wound area over time. After six weeks, wounds had closed by a median of 75%, and after 12 weeks 95% wound healing had been achieved. Importantly, transplanted wounds were completely closed after one year.

Time since stem cell transplant had no influence on the efficacy of skin grafts, but researchers said that head and neck wounds tended to close faster (100% wound closure after 12 weeks) than those on the trunk or extremities.

One participant also underwent surgery to separate the fingers from both hands — which tend to stick together as a result of skin wounds in RDEB patients — and received grafts on the palms and fingertips. Grafts “showed excellent early take and stability over time,” the investigators wrote.

Over the trial period, patients and caregivers did not report a significant improvement in quality of life or a lessening of symptoms such as pain and itching. The researchers believe this is “likely secondary to the overall limited body surface area addressed in this trial,” they wrote.

The approach was overall safe. Donor sites healing quickly with only mild and transient loss of skin color were reported in half of all donors. One patient developed metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma outside the transplanted skin area.

Notably, the grafts in these patients persisted beyond the usual lifespan of epidermis (48 days) and had a much greater contribution from donors than initially expected, which researchers described as “intriguing.”

They suggested that the transplanted epidermis contained some skin progenitor cells, which continued to give rise to donor skin cells in the graft region. An additional explanation, which has been observed in other skin transplant studies, is that bone marrow-derived epithelial cells were recruited to the graft site and helped to support wound healing.

These findings showed that “epidermal allografting [graft from a donor] in RDEB provided both excellent functional wound repair and intriguing evidence of stimulated local epidermal proliferation,” the researchers wrote.

And, they added, “successful allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant establishes immune tolerance for secondary tissue grafts from the same donor, herein demonstrated with skin grafts.”